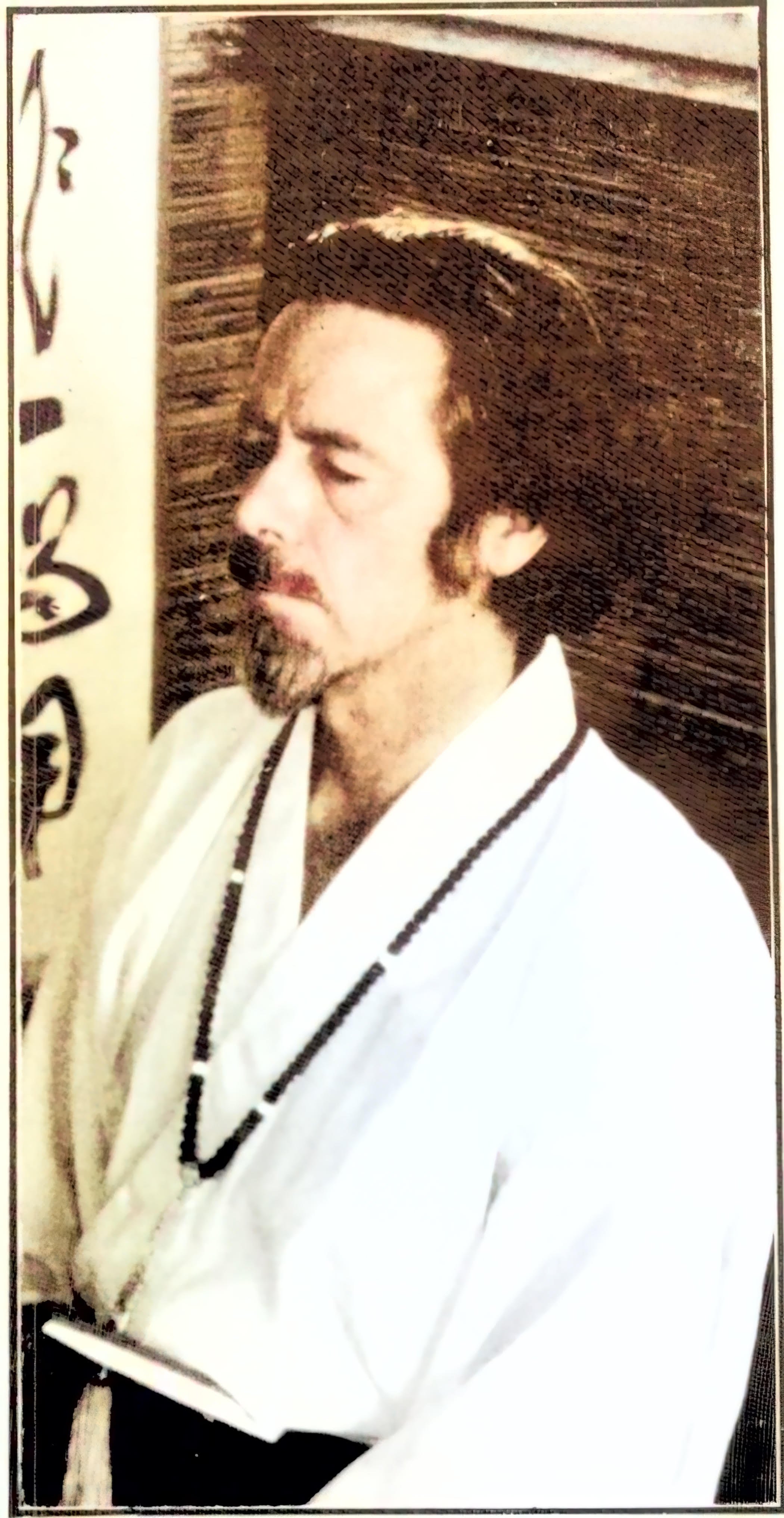

ALAN WATTS BIOGRAPHY

Who is Alan Watts?

LIFE: As a prolific writer and speaker during the 1960’s, Alan Watts was one of the first to interpret Eastern wisdoms for Western audiences. After gaining recognition as an author in the mid-50’s, he lectured widely in the 60’s and early 70’s, offering a fresh perspective of the human predicament based on the philosophy and psychology of Eastern religion. His worldview took into account the revelations of modern sciences including ecology, contemporary explorations in mysticism, and the classic ways of liberation practiced in Asia, including Zen, Taoism, Hinduism and Buddhism at large.

Before he was adopted as a spiritual figurehead by the counterculture, he became a priest 1940’s, and a professor and later Dean at the Academy of Asian Studies in the early 1950’s. By the mid 50’s he was gained recognition as a leading voice of the Zen-Boom, largely due to his popular Bay Area radio show, Way Beyond the West, His 1957 bestseller, The Way of Zen brought national recognition, and in 1959 the first season of the public television show, Eastern Wisdom and Modern Life lead to a feature article in a Look magazine article, which visited him working at home, surrounded by his children. By the early 60’s he was going out on speaking tours regularly, visiting various colleges and universities, and began record his talks. The recordings we then featured in his weekly radio series, and re-broadcast in cities across the US. He went on to become a luminary to the counter culture movement, and appeared again on national television in 1972.

PHILOSOPHY: When he spoke Alan Watts did not advocate self-improvement— instead he was promulgating self-understanding. He never claimed to be anything other than a playful observer or a philosophical entertainer, and didn’t endorse a particular path or behavior, but encouraged listeners to consider a variety of worldviews. Instead of advocating for a single method he felt the direct experience of reality, and ‘triangulation’ one’s position by comparing the views of diverse cultures, including the traditional cultures of the Far East, was for him a fruitful methodology. In his final television appearance he brought these observations together, pointing to the inevitable unity with nature or ‘what is so of itself’’ in which humanity is embedded. Seeing nature as the essential qualities or Tao of things, he focused on the idea of ‘mutual arising’, and pointed out the intelligence of navigating with course, current and grain of nature, which he called the ‘watercourse way’ He also often referred to the art of ‘upaya’, or skillful means, and of putting up a sail to catch the winds of nature instead of pushing through with the force of human endeavor.

The Early Years (1915-1939)

Alan Watts was born in England on January 6, 1915, and lived with his parents outside of London in the small town of Chislehurst. He was a naturally curious child, and at a young age Alan began questioning many of the things that most people took for granted. His mother taught at a nearby boarding school where her students were mostly children of missionaries to China, and upon their returned from Asia they often brought gifts of Chinese and Japanese art. These pieces filled the Watts’ parlor, and Alan became fascinated by the vision of nature that he saw in the miniature painted landscapes and decorative ceramics. Recognizing his bright and inquiring nature, his parents encouraged Alan to write, his father would bring Alan to the Buddhist Lodge in London, where as a teenager Alan became editor for the Lodge’s journal, The Middle Way. In 1932, he produced his first booklet at age 16, An Outline of Zen Buddhism, and his first book, The Spirit of Zen five years later. During this period he spoke frequently art the Lodge, where he met DT Suzuki and Christmas Humphries and engaged in a rich dialog about Eastern philosophies. In 1938, Alan moved to the United States to study Zen in New York, and there he soon began lecturing in bookstores and cafes. However this was to be a trial run, and a time to experiment. Growing up in England he was initially educated to become a priest in the Church of England, but by his early teen reading of book of Glimpses of Forgotten Japan by Lagcadio Hern, and also the Fu Manchu captured his imagination instead. As he later recounted, “Other children wanted to grow up to be engineers or race car drivers, but I wanted to become a mysterious Chinese villain”.

The Middle Years (1940-1959)

In New York his lectures attracted the interest of a publisher, and 1940 The Meaning of Happiness was published, a book based on his talks. Ironically, the book was issued on the eve of the second World War, at a time when happiness was not a topic on most people’s minds. So after his brief time in New York, Alan moved to Chicago and enrolled at Seabury-Western Theological Seminary, deepening his interest in mystical theology. He was ordained as an Episcopal priest in 1944, and became the Chaplin for Northwestern University. However his messages from the pulpit were unorthodox, and by the spring of 1950, Alan’s time as a priest had run its course. He left the Church and Chicago for upstate New York, where he settled into a small farmhouse outside Millbrook, and began writing The Wisdom of Insecurity: A Message for an Age of Anxiety.

In early 1951 Alan relocated to San Francisco, where, at Dr. Frederic Spiegelberg’s invitation, he began teaching Buddhism at the American Academy of Asian Studies. His classes at the Academy were popular, and soon blossomed into evening lectures open to the public, which in turn spilled over to local coffee houses frequented by Beat poets and writers. Alan’s career took to the airwaves in 1953, when he accepted a Saturday evening slot on Berkeley’s KPFA radio station. That year he began a broadcast series titled “The Great Books of Asia” followed in 1956 by “Way Beyond the West” — which proved to be very popular among Bay Area audiences. Re-broadcast on Sunday mornings, the show aired on KPFK in Los Angeles as well, beginning the longest-running public radio series — nearly 60 years at this writing. By the mid-fifties the “Zen Boom” was well underway as Beat intellectuals in San Francisco and New York began celebrating and assimilating the esoteric qualities of Eastern religion into an emerging worldview that was later dubbed “the counterculture” of the 1960’s. In many ways 1959 was a breakout year for Alan—his book Nature Man and Woman was released to critical acclaim, and the first season of his television series Eastern Wisdom and Modern Life aired nationally.

The Later Years (1960 to 1973)

Throughout the 1960’s Alan lectured at colleges and Universities throughout the U.S. and Canada, and conducted seminars at fledging “growth centers” across the country, including the world-renowned Esalen Institute of Big Sur, where together with Gregory Bateson he gave a founding lecture in 1963. In 1964 he spent a few weeks speaking at the coastal California enclave, followed by an extensive lecture tour in 1965, with notable stops at SMU in Dallas and at The Richmond Theological Seminary in Virginia. The 1966 publication of The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are, saw him take to the road again, this time touring Canada and the Northeast. The Book sold well, and requests for appearances poured in. During this period broadcasts of his live recordings continued at KPFA and KPFK, and gained large audiences on WBAI in New York and WBUR in Boston. As the weekly shows attracted a wide audience and Alan gained recognition as a pivotal figure in the counterculture movement, and the San Francisco Bay Area became a hotbed for radical politics, and a focal point of interest in Far Eastern ideas of enlightenment and liberation. As the movement gathered steam, the growing tide united civil rights activists, antiwar protesters, and members of the Free Speech movement, drawing thousands of young people to the Bay Area in 1967. After his stirring performance of Zen Bones at a “Zenefit” for the San Francisco Zen Center in 1967, and a celebrated article on “Changes” in the Oracle alternative newspaper, Alan became a defacto spiritual figurehead of the revolutionary movement. Interest in psychedelics was at an all time high, and having experimented with LSD and psilocybin earlier in the cycle, he advocated a balanced approach, suggesting that “once you get the message, hang up the phone.”

By the late-sixties Alan was living on a ferryboat in Sausalito in a waterfront community of bohemians, artists, and other cultural renegades just north of San Francisco. The ferryboat soon became a popular destination and to maintain a focus on writing, Alan moved into a cabin on the nearby slopes of Mount Tamalpais. There he became part of the Druid Heights artist community while continuing to travel on lecture tours into the early seventies. He was increasingly drawn to life on the mountain, where he wrote his mountain journals (later published as Cloud Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown), and penned his monograph The Art of Contemplation. During this period he also finished his autobiography In My Own Way, and wrote his final book, Tao: The Watercourse Way. After returning from a whirlwind lecture tour that took him through the U.S., Canada, and European, Alan passed away in his sleep on November 16, 1973, on the mountain he loved.